Four Letters of Love – Film Review

Published August 2, 2025

Four Letters of Love arrives with the pedigree of a celebrated novel, a strong cast of veteran actors, and a sweeping premise about destiny and the inevitability of true love. Directed by Polly Steele, with the screenplay adapted by author Niall Williams from his own work, the film follows Nicholas Coughlan and Isabel Gore — two people seemingly meant for each other. Yet, their union is anything but straightforward. Fate, ghosts, and the mysteries of love conspire to bring them together, while the unpredictable events of life threaten to keep them apart.

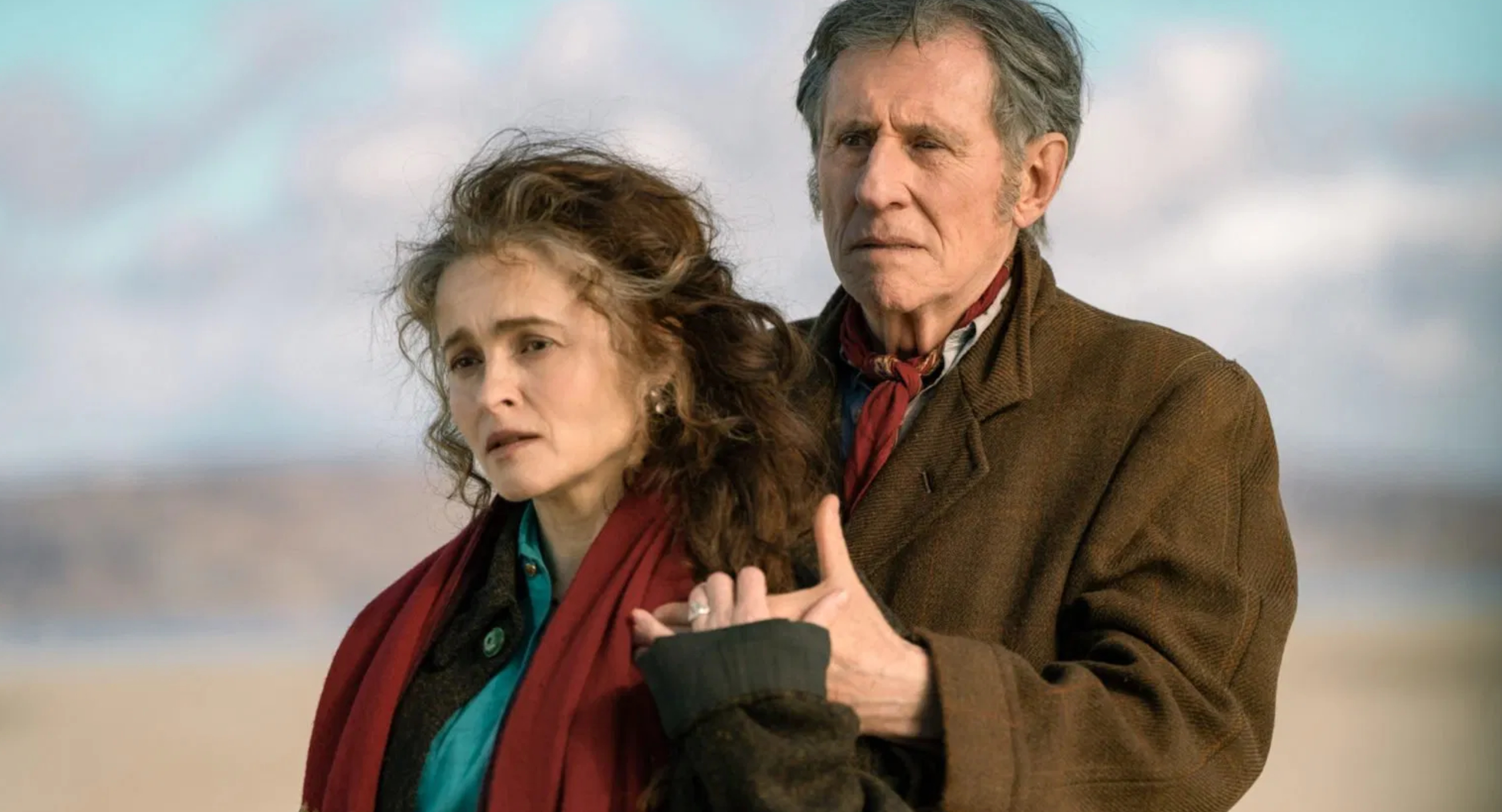

The story’s narrative frame is filtered through other lives — Pierce Brosnan plays William Coughlan, Nicholas’s father, and Helena Bonham-Carter and Gabriel Byrne portray Isabel’s parents, Margaret and Muiris Gore. This focus on family dynamics, tragedy, and the strange pull of destiny gives the film an unusual structure, one that strives for poetic beauty rather than conventional plotting.

If nothing else, Four Letters of Love looks exquisite. Cinematographer Damien Elliott paints the Irish landscapes with painterly detail — rolling green hills, windswept coastlines, and rustic interiors bathed in warm amber light. Each frame seems designed to be hung on a gallery wall, and the use of natural light lends the film a dreamlike quality.

The problem is that this beauty rarely translates into emotional momentum. Steele lingers on quiet moments — a look across a field, a pause before a door is opened, a hand brushing against a windowpane — but these instances, while gorgeous, often stall the narrative. The pacing is languid to a fault, and while some will appreciate the meditative approach, many will find it drags, draining urgency from a story that’s meant to be about love’s irresistible force.

On paper, the casting is irresistible. Brosnan, Bonham-Carter, and Byrne bring decades of craft to the table. Brosnan’s William is reflective and understated, portraying a man caught between the demands of his own life and the ethereal pull of fate. Bonham-Carter gives Margaret a fragility tinged with sharp wit, while Byrne imbues Muiris with a stern gravitas that hints at deep wells of vulnerability.

And yet, the emotional connections feel oddly muted. The performances are technically strong, but the film rarely lets them breathe in a way that fosters organic chemistry. Ann Skelly’s Isabel is luminous and watchable, but her scenes with Nicholas (played by Fionn O’Shea) lack the charged spark that should make their destined love compelling. This absence of palpable passion is a serious flaw in a romance so dependent on the audience believing in a grand, fated connection.

Adapting one’s own novel can be a double-edged sword. Williams clearly understands the thematic threads of his story, but he also seems unwilling to cut or reshape them for cinematic purposes. The result is a script that is faithful to the book’s prose but often feels inert on screen. Where a novel can luxuriate in internal monologues and lyrical descriptions, a film needs sharper economy and externalized emotion.

Scenes that might have been moving on the page — such as quiet domestic moments, fleeting supernatural encounters, and long reflective conversations — sometimes land flat here. There’s a persistent sense that the screenplay is trying to capture the novel’s poetry without finding a visual or structural equivalent in film language.

This should’ve been a sweeping, heart-swelling story about love’s inevitability and the forces that keep us apart until the right moment. Unfortunately, despite its beauty, the film rarely evokes the kind of deep emotional reaction it aims for.

Part of the problem is that the central romance exists more in the abstract than in lived experience. Nicholas and Isabel’s connection is described, implied, and fated, but not deeply shown through shared moments that allow the audience to feel their love developing. We’re told they’re made for each other, but the film struggles to prove it to us.

Polly Steele clearly has a delicate, lyrical vision for the film. Her restraint avoids melodrama, but it also sometimes smothers the potential for powerful emotional highs. The tone is consistently wistful, the pacing consistently slow, and the mood consistently gentle — all of which can work, but here they leave the story feeling monotonous.

Moments that should be pivotal — an encounter that could change everything, a tragedy that alters the course of lives — come and go without the visceral impact they need. It’s as if the film is so determined to maintain its hushed, elegant tone that it refuses to let anything truly disrupt it.

From a technical standpoint, Four Letters of Love is polished. Conroy’s cinematography, as mentioned, is a highlight, and the production design captures a romanticized vision of Ireland that feels timeless. The costume work is equally strong, grounding the film in a believable sense of place.

The score, while pleasant, tends toward the predictable — soft strings, melancholic piano, and sweeping orchestral swells that feel lifted from a generic romance template. It underscores the scenes without elevating them, leaving little musical identity behind.

Four Letters of Love had the ingredients to be something special: a beloved source material, a cast of acclaimed actors, and the potential for a visually and emotionally rich tale of love and destiny. Unfortunately, the film gets lost in its own reverie, prioritizing poetic stillness over emotional engagement.

While it may find an audience among those who enjoy slow, meditative romances steeped in atmosphere, it ultimately falls short of delivering a truly moving experience. By the time the credits roll, the audience may admire the beauty they’ve seen but feel little of the passion they were promised.