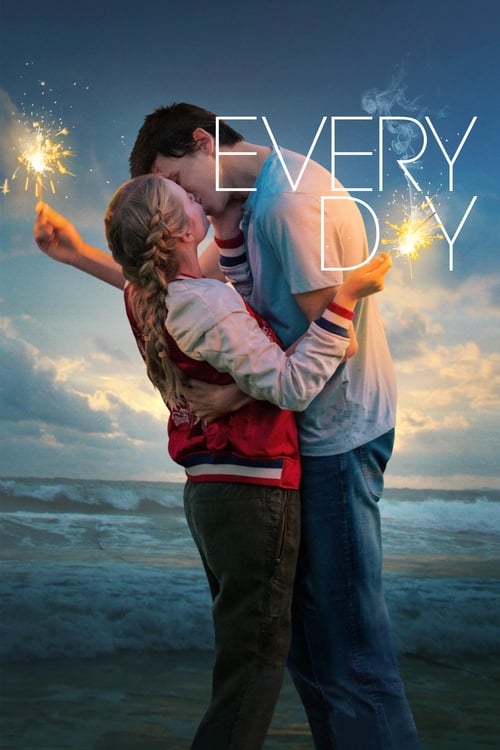

Every Day – Film Review

Published May 11, 2025

The 2018 film Every Day, directed by Michael Sucsy and based on the bestselling young adult novel by David Levithan, sets out with an ambitious and emotionally resonant premise: a mysterious soul named “A” wakes up in a different body every day and falls in love with a teenage girl. While the concept carries immense potential for introspection, empathy, and complexity, the film ultimately squanders it on a muddled narrative, underdeveloped characters, and a saccharine teen-romance formula that lacks the courage to grapple with the moral and philosophical implications of its own story.

At the heart of Every Day is “A,” a genderless, bodiless being who inhabits a different sixteen-year-old’s body every morning. One day, “A” wakes up in the body of Justin (Justice Smith), the neglectful boyfriend of Rhiannon (Angourie Rice). Unlike Justin, “A” is tender, present, and deeply attentive, and this striking change in behavior during one shared day at the beach causes Rhiannon to fall for the person inside—not the body. From then on, “A” reveals their reality to her and attempts to reconnect each day in whatever new body they inhabit.

On paper, this is a deeply intriguing concept, one that challenges our assumptions about identity, attraction, and love. Can you truly love someone whose body and life changes daily? What does it mean to know someone? And how ethical is it to act on affection when the person you’re borrowing doesn’t consent to your choices? These are urgent, layered questions, but the film doesn’t seem all that interested in answering them. Instead, it chooses the path of least resistance—focusing on the surface-level novelty of “A’s” condition and framing the story within a tidy, cliché-ridden teen romance.

Angourie Rice delivers a grounded and sincere performance as Rhiannon, anchoring the film with the necessary emotional continuity. Despite the implausibility of the premise, Rice somehow maintains believability in her reactions and emotional arcs, bringing vulnerability to a character who is otherwise written quite plainly. Her confusion, wonder, and eventual frustration with “A” are some of the film’s few emotionally honest moments.

Justice Smith, Lucas Jade Zumann, Jacob Batalon, and a carousel of other young actors play the various bodies inhabited by “A.” While this rotating cast highlights the inclusivity and diversity inherent to the concept (with actors of different races, genders, and body types), it also makes it nearly impossible to sustain any lasting chemistry. Some actors fare better than others in capturing the gentle, philosophical demeanor of “A,” but the disconnect between body and essence often feels more distracting than poignant.

Director Michael Sucsy, known for The Vow, brings a glossy, overly sanitized aesthetic to the film, flattening what should be a weird, wild, disorienting experience into a pastel-toned YA package. Everything is too clean, too nice, too inoffensive. The film is so focused on being agreeable that it forgets to be challenging or thought-provoking. The tone rarely strays from gentle sentimentality, and the stakes never feel real—even as we’re told that “A” has lived thousands of different lives and is grappling with a cosmic burden.

There are opportunities for genuine conflict—especially as Rhiannon begins to question what it means to be with someone who will never be the same person twice in a row—but the film never pushes these tensions to a meaningful breaking point. Even a potentially disturbing scene where “A” makes a decision involving a suicidal body is handled with an odd breeziness that diminishes its weight.

The screenplay, adapted by Jesse Andrews (who also wrote Me and Earl and the Dying Girl), tries to capture Levithan’s introspective voice, but it translates poorly to screen. The dialogue often sounds overwritten and overly articulate for teenagers, attempting poeticism but landing flat. “A” constantly speaks in grand abstractions about love and identity, but the film doesn’t offer concrete, lived-in examples of these ideas—it tells rather than shows.

More frustratingly, the film glosses over the logistics and ethics of “A’s” condition. We’re told that “A” never does harm and avoids interfering with people’s lives—but that’s clearly untrue, as “A” often makes people skip school, lie to their families, or abandon their routines for hours to be with Rhiannon. At one point, “A” takes over the body of Rhiannon’s own friend, effectively hijacking their dynamic without consent. These moments, which should raise serious red flags, are waved away with romantic platitudes and the assumption that love justifies everything.

Every Day attempts to be progressive in its portrayal of love as something that transcends gender, race, and appearance, which is commendable. “A” inhabits both male and female bodies, offering the rare sight in a mainstream film of a teenage girl kissing a girl or an overweight boy or someone outside the conventional romantic norm. But the execution feels cautious, like the filmmakers want to check off diversity boxes without fully embracing the implications.

There’s a scene where Rhiannon, after days of being with “A” in different bodies, meets “A” in the form of a trans teen. Instead of using this moment to explore the depth of “A’s” experiences—or Rhiannon’s own preconceptions—the film shrinks from the conversation, brushing past it quickly. This unwillingness to confront anything too complex or controversial undermines the very message of unconditional love the story wants to convey.

The final act does little to rectify the thematic confusion. Rather than providing an emotionally satisfying resolution or a bold narrative choice, the film ends on a note of safe ambiguity. It gestures toward selflessness, but without reckoning with the deeper consequences of either Rhiannon’s or “A’s” actions. By the end, it feels as though Every Day is more interested in delivering a mood than a message.

Every Day deserves credit for its unique premise and for trying to bring diversity and metaphysical thoughtfulness to the often formulaic teen romance genre. But despite its ambitions, the film never rises above its own limitations. It’s emotionally earnest, visually polished, and well-meaning, but those qualities alone aren’t enough to make up for a script that’s afraid to dig into its own questions.

Ultimately, Every Day is a film that flirts with depth but settles for sentimentality. It offers a glimpse of something bold and transformative but delivers something bland and forgettable. For a story about love unbound by physical form, it’s disappointingly conventional in every other way.