Wuthering Heights – Film Review

Published February 19, 2026

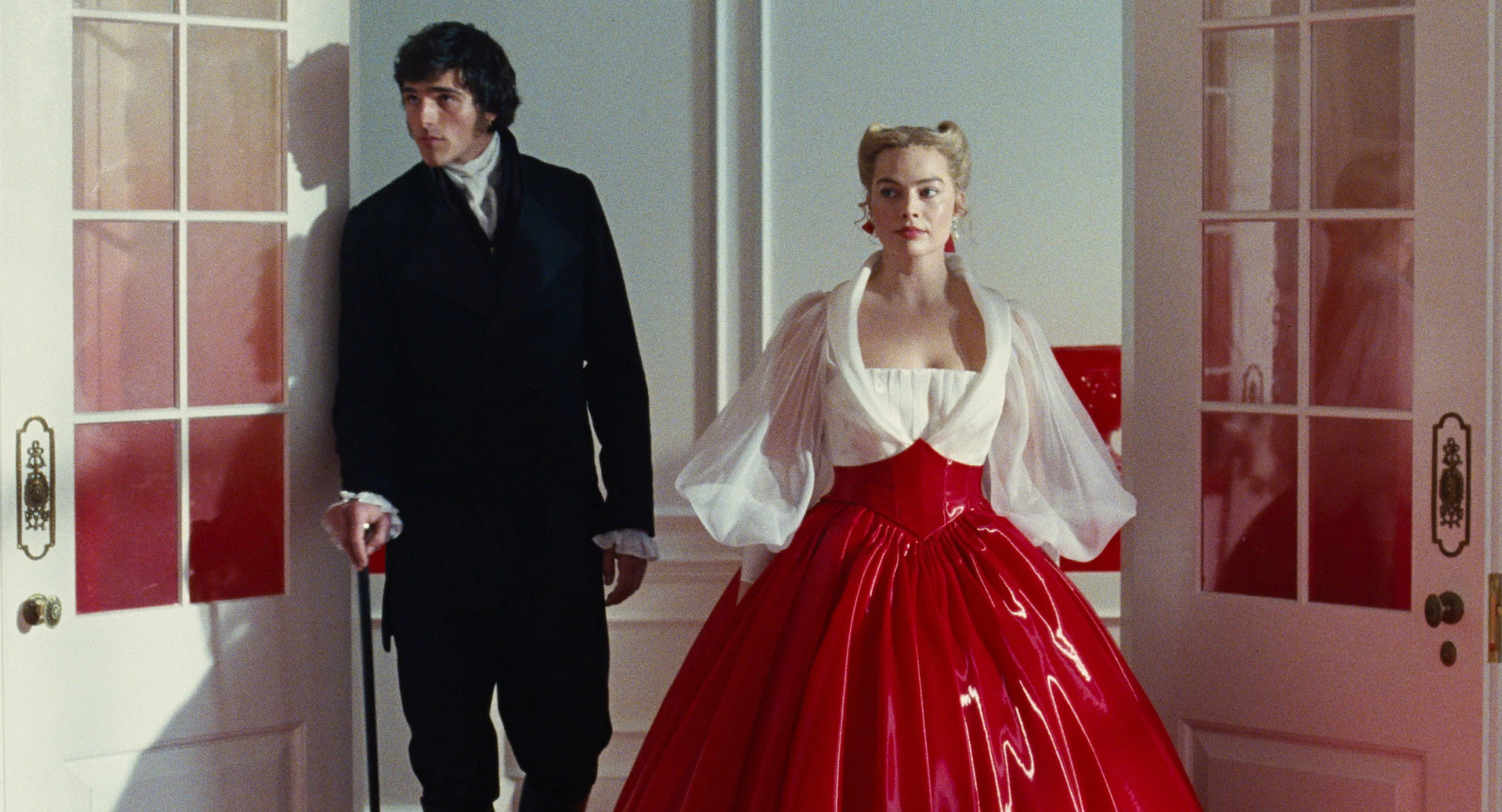

Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights arrives swathed in mud, velvet, and provocation. Written for the screen, co-produced, and directed by Fennell, this take on Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel trades windswept melancholy for feverish eroticism and operatic cruelty. With Margot Robbie as Catherine Earnshaw and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff, the film promises a combustible romance for modern audiences. Instead, it delivers a visually striking but dramatically hollow spectacle that mistakes extremity for emotional depth.

Fennell, known for her sharp tonal control and subversive impulses, leans heavily into decadence and transgression. From its shocking opening sequence to its final tragic tableau, this Wuthering Heights is determined to unsettle. Yet in its eagerness to provoke, it loses sight of what made Brontë’s story endure: psychological intimacy, moral ambiguity, and the slow-burn corrosion of love into obsession.

There is no denying the film’s visual power. The Yorkshire moors are rendered in bruised purples and slate greys, the wind howling through dilapidated corridors like a restless spirit. Wuthering Heights itself becomes a character—rotting, oppressive, and increasingly claustrophobic as the Earnshaw household decays. Fennell and cinematographer Linus Sandgren frame bodies like paintings: skin luminous against dark wood, candlelight flickering across tear-streaked faces.

Yet the film’s aesthetic boldness often feels self-conscious. Moments that should be intimate are staged with a theatrical grandiosity that distances the viewer. The erotic charge between Cathy and Heathcliff is presented in explicit, confrontational terms, but the emotional groundwork that would make such passion resonate is surprisingly thin. Their connection is told to us through intensity rather than built through shared vulnerability.

Margot Robbie’s Catherine is feral and mercurial, oscillating between cruelty and childlike longing. Robbie commits fully, delivering a performance that is both physically daring and emotionally volatile. However, the script rarely allows her quieter moments of introspection. Catherine’s internal conflict—her struggle between social ambition and wild devotion—feels abbreviated, reduced to a handful of feverish speeches rather than a gradual unraveling.

Jacob Elordi brings a magnetic physical presence to Heathcliff. His transformation from abused outsider to groomed, vengeful aristocrat is visually striking, and Elordi captures the character’s simmering resentment with brooding intensity. Still, the film simplifies Heathcliff’s psychology. His rage, jealousy, and cruelty are foregrounded, but his wounded romanticism—so essential to understanding his obsession—is underexplored.

The supporting cast offers flashes of nuance. Hong Chau’s Nelly Dean is perhaps the film’s most grounded presence, observing the chaos with a mixture of loyalty and moral unease. Shazad Latif’s Edgar Linton is rendered as polished but emotionally fragile, a man outmatched by the elemental force of Cathy and Heathcliff’s bond. Alison Oliver’s Isabella, meanwhile, becomes a vessel for the film’s most uncomfortable provocations, her infatuation curdling into something deliberately disturbing.

Fennell’s decision to amplify the novel’s darker elements results in sequences that feel more sensational than revealing. Scenes intended to shock—whether sexual, violent, or psychologically cruel—often overshadow character development. The result is a film that seems enamored with its own audacity.

What ultimately undermines this adaptation is its imbalance. The love between Cathy and Heathcliff is meant to feel mythic and all-consuming. Instead, it frequently comes across as toxic spectacle. The script emphasizes degradation, jealousy, and revenge but offers fewer glimpses of the tenderness that might justify such destructive devotion.

The pacing contributes to this problem. Key emotional beats arrive abruptly, giving the impression of narrative compression. Cathy’s decision to marry Edgar, Heathcliff’s departure and return, and the escalation of their affair unfold with operatic speed. Without the novel’s layered narration and generational scope, the story feels streamlined in a way that sacrifices depth for intensity.

Even the film’s most tragic turns lack the cathartic weight they should carry. Fennell frames suffering in stylized compositions, but the cumulative effect is numbing rather than devastating. The audience observes the characters’ misery from a distance, impressed by the craftsmanship yet unmoved by the outcome.

Loose adaptations can thrive when they reinterpret classic material with insight. Fennell’s Wuthering Heights certainly reinvents Brontë’s work, foregrounding sexuality and class anxiety in bold strokes. However, the thematic exploration of social mobility and gendered constraint remains surface-level. Catherine’s desire to ascend into wealth and refinement is visually signified—through lavish gowns and ornate interiors—but her internal rationale feels underdeveloped.

Similarly, Heathcliff’s rise to fortune is presented as a dramatic flourish rather than an organic evolution. The mystery of his transformation could have been fertile ground for exploring resentment and ambition. Instead, it becomes another stylized pivot point in a story already crowded with heightened moments.

The film’s production design deserves praise. Thrushcross Grange, in contrast to the decaying Heights, gleams with suffocating opulence. Catherine’s room, designed to mirror her own skin tones, is an unsettling touch that underscores the film’s fixation on corporeality and possession. Yet such visual metaphors often substitute for emotional clarity.

Robbie and Elordi share undeniable screen chemistry, but their performances are constrained by a script that prioritizes spectacle. When given space, they hint at the aching connection beneath the chaos. A fleeting glance across a windswept field or a whispered confession carries more power than the film’s most explicit encounters. Unfortunately, these moments are too rare.

Hong Chau emerges as a quiet standout. Her Nelly anchors the narrative, offering a perspective that balances empathy and critique. Chau’s restraint contrasts sharply with the operatic excess surrounding her, highlighting how much more affecting the film might have been with a steadier hand.

The supporting ensemble—including Shazad Latif and Alison Oliver—navigate challenging material with commitment, though their characters often feel like extensions of Cathy and Heathcliff’s turmoil rather than fully realized individuals.

Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights is undeniably ambitious. It seeks to drag Brontë’s stormy romance into visceral, modern territory, emphasizing eroticism and brutality with unflinching boldness. There are moments of genuine visual poetry and committed performances that suggest a more cohesive film lurking beneath the surface.

However, the adaptation ultimately prioritizes shock over substance. By amplifying the most extreme elements of the story while sidelining its emotional intricacy, the film reduces a timeless tragedy to a parade of heightened tableaux. It is beautiful to look at and occasionally compelling in its performances, but it rarely captures the aching inevitability that defines the original tale.

In striving to be provocative, this Wuthering Heights loses the haunting intimacy that made Brontë’s novel endure. The wind still howls across the moors, but the heartbreak it carries feels strangely distant.